The story of the green children of Woolpit was originally written in Latin by two English monks, Ralph of Coggeshall and William of Newburgh.* When writing my fictionalized account, I commissioned translations for both versions, and I was struck by the small variations between these and other published accounts I ran across.

The translator was kind enough to share her notes and give permission for them to be reproduced here so others can see the way in which sources are unstable and often reflect bias in ways that might not be readily apparent. In other words, there is no such thing as an “accurate” translation. Texts are subject to interpretation at many different points in their creation and transmission, and translation is often a moment when these issues can be explored in detail.

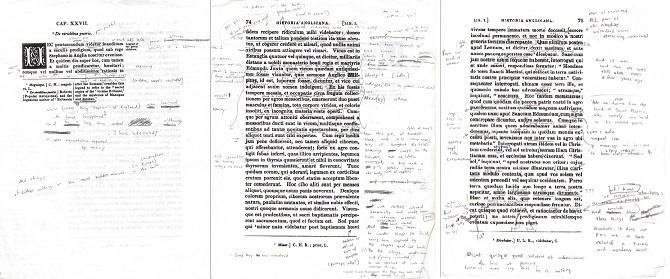

Below is a rough copy of the translator’s work as she reviewed the material. (The version shown here is William of Newburgh’s.) Here, the translator is identifying the words and the different ways they could potentially go together.

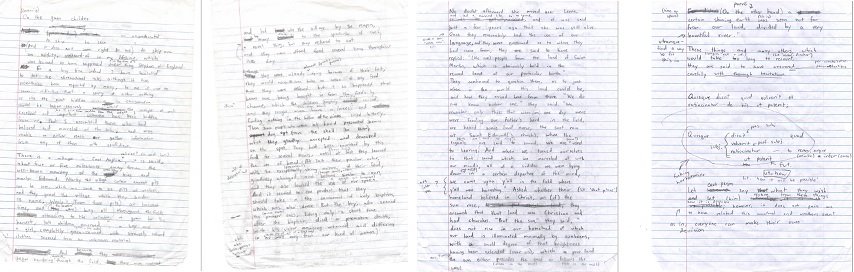

Below is a more final version in which the translator smooths the fragmentary language into sentences that flow logically to an English-speaking reader.

This is also when the translator was able to resolve issues she identified in the rough edition of the text; by viewing the words and their order holistically, it’s easier to determine the story they’re trying to tell. This lets the translator make good decisions in terms of word choice, idiom, and overall style. The idea here is to capture the original author’s meaning and communicate it to an audience that is used to experiencing language in an entirely different way.

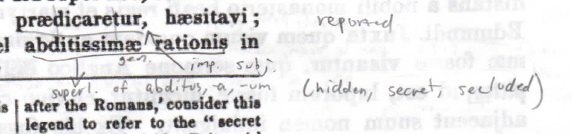

For instance, a word often has more than one potential meaning. According to the translator’s notes, the word “abditissimae” could mean “most hidden,” “most secret,” or “most secluded.” These words all mean generally the same thing, but each has nuances to them that would change the meaning, sense, or tone of the idea as a whole. Choosing which of these specific words most closely captures what the monks might have meant is not as simple as it seems.

You can read the final translation of William of Newburgh’s account here, and that of Ralph of Coggeshall here.

The story of the green children of Woolpit is an old one, and so much about it relies on interpretation. It’s worth noting, too, that neither of the monks was an eyewitness to the events he wrote about. Neither one met the green children in person. So even their account is subject to translation. Right from the beginning, we can’t be sure what was left out, what was included, and what exact, specific words were used by the folks who told them the story.

Right from the beginning, the story of the green children of Woolpit was somewhat lost in translation.

*For a thorough history of the provenance of each medieval account, please see John Clark’s The Green Children of Woolpit, pp. 8-17